Movement: Hip-Hop in L.A., 1980-Now

Centerpiece for museum exhibit catalog

With the landslide elections of actor and former California Governor Ronald Reagan to the presidency in the 1980’s, Hollywood was officially in the (White) House – and became the unofficial capital of America. With his conservative right wing agenda, Reagan threw up a dub for the Westside, as Reaganism went big time under the lights of the new Hollywood-Beltway axis. With his deep and powerful connections to Hollywood, L.A. in the 1980’s and ‘90’s replaced 1970’s New York as the national symbol of urban decay – as “welfare queens,” crack dealers, gang wars, “riots,” and “illegals” represented threats to domestic order that Reagan’s crusade wanted to eliminate.

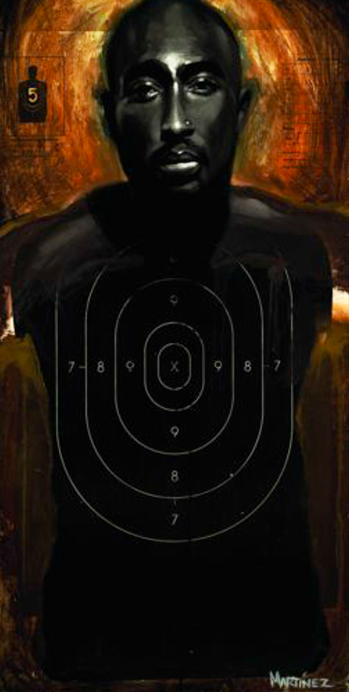

Hip-hop arose phoenix-like from the ashes of 1970’s New York, and in the 1980’s, the hip-hop generation wasn’t going to be victims of media politrix. As they struggled for exposure when film, television and even Black radio dismissed them, Chuck D’s claim that hip-hop was the “Black CNN” only told part of the story. Because hip-hop was more than that – it was pirate radio and guerilla cinema, talking book and subversive theory, political theater and radical public art. In essence, it was an aesthetic vanguard and a chin check to white America. And before the current babble about the ‘mainstream’ vs. the ‘underground,’ hip-hop was both – and it was neither. It was Basquiat and Marcus Garvey tagging history’s walls. Cheikh Anta Diop and Rakim building in a cipher. King Tubby and Premier on the SP. Harriet Tubman and Ras Kass sharing secrets. And Patrice Lamumba and Pac doing the knowledge.

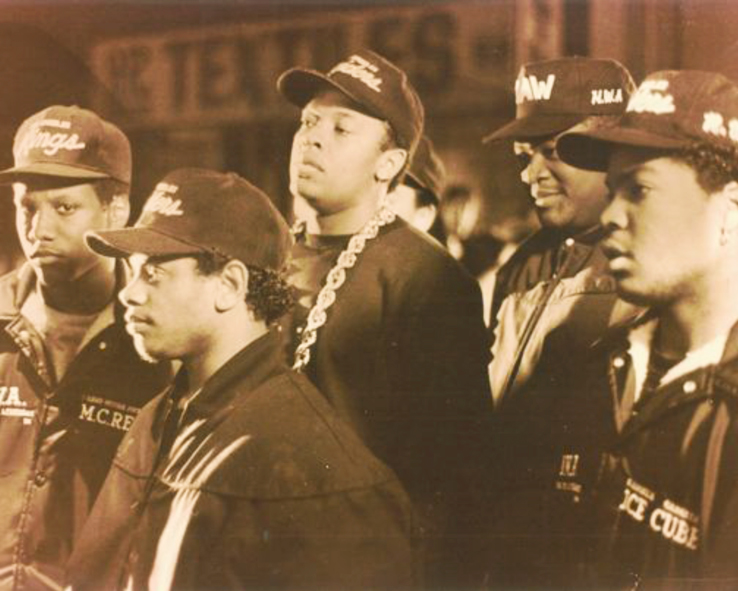

With Reaganism’s foot on the gas, the G-ride it rolled in had L.A. police Chief Daryl Gates riding shotgun. A cross between Bull Connor and Dirty Harry, Gates’ militaristic policing got cover from the “War on Drugs” and Hollywood with films like Colors – where L.A. was projected as a violent, gang-ruled city – and later Falling Down – which heightened the national panic around L.A., using a sympathetic white vigilante in the tradition of John Wayne and Travis Bickle. In creating an alarmist tone of L.A. as dystopia and whiteness under siege, these flicks presented the LAPD as heroic violent redeemers restoring order to the city’s chaos.Hip-hop in L.A. emerged from this surreal landscape and vicious geography of violence. Not surprisingly the rags-to-riches fantasies that marked early East Coast hip-hop gave way to the grams-to-Grammy ethos that now dominates hip-pop – a battle cry that could only have come from the wicked fusion between Hollywood and L.A.’s crack economy. As cocoa crops got imported to local blocks, the vivid tales and documentary realism of street life couched as sonic fantasy got put on wax, eerily coinciding with hip-hop becoming more profitable and palatable to suburban voyeurs.It’s this kind of profane mathematics that made the cinematic tales of Ice-T, N.W.A., and others burn with urgency. When N.W.A. released Straight Outta Compton in 1988, the album was blistering in its defiant portrayal of the sufferers in post-industrial L.A., underclass Black life, and the policing that held it together – as it radically redrew the borders between nihilism and rebellion in hip-hop. If G Rap’s “Streets of New York” and Nas’ “N.Y. State of Mind” were the soundtrack to the rotting Apple of the ‘80’s and ‘90’s, Straight Outta Compton stands as L.A.’s declaration of war. Not because the FBI protested them. But because N.W.A. put the LAPD on trial – a radical form of political theater that symbolically sought redress for centuries of racial injustice, while opening a debate and revealing a gaping wound about race, policing and prisons in the country.

As the lyrical genius behind N.W.A., Ice Cube continued blurring the lines between celluloid, wax and prophesy. When he lyrically laid to waste Chief Gates on Death Certificate, it was both collective redemption and Hollywood fantasy, Nat Turner and Sweetback coming back to collect some dues. But with the Rodney King verdict and the 1992 Uprising, it wasn’t until Dre dropped The Chronic that L.A. got put on blast and revealed not as the whitewashed utopia it fronted as, but as the powder keg its always been. Hollywood tried to capture the mayhem with Boyz N the Hood, American Me, Deep Cover and Menace II Society. While presenting more complexity to the lives of Black and Brown youth than usual, these flicks revealed a claustrophobia, violence and nihilism that not only rendered L.A. unlivable, but escape impossible – except through death. Even visually, L.A. for urban youth was a prison, their lives cinematically “captured” for viewing pleasure.

But outta the gangsta silhouette of L.A.’s mean streets was the equally relevant hip-hop inspired by Project Blowed/KAOS, the Good Life Café, and others who were the children of New York’s The East, and L.A. native son Horace Tapscott’s UGMAA (Union of God’s Musicians and Artists Ascension). But possibly Project Blowed and Good Life’s most enduring connection is to the L.A. School of Black Filmmakers that emerged in the 1970’s, including Haile Gerima, Charles Burnett, Larry Clark, Ben Caldwell and others who were influenced by Third World cinema, Black liberation politics and a desire to challenge Hollywood’s degrading images of Black people. Gerima’s Bush Mama (1976), Clark’s Passing Through (1977) and Burnett’s Killer of Sheep (1977) are incredible films that used L.A. as their Blackdrop, and they embody so much of the spirit of Freestyle Fellowship, Medusa, and Divine Styler, as well as Jurassic 5, Dilated Peoples, the Beat Junkies and the Pharcyde.

While many of these heads came up with the spotlight on L.A.’s gangsta politics, some of us forget the brilliance of their work (don’t sleep on Freestyle Fellowship’s debut To Whom It May Concern). What made these artists so influential and memorable was not that they were able to escape the crucible of racial violence in L.A. – because they couldn’t. It was because they made dope records. They channeled their creative impulses onto wax when this thing called the “hip-hop industry” was cementing itself around narrow definitions of hip-hop, especially on the West Coast.

But that’s what makes hip-hop, and especially L.A. hip-hop so powerful: it remixed the ideas and images of Black people being beamed from media conglomerates and spit it back to them, bringing the theater of war to wax by writing themselves into existence and imagining their own liberation, where Black people went from wretched of the earth to cream of the planet. Whether it’s Snoop or Planet Asia, Cube or J5, all these MC’s span the continuum of black creative genius, encompassing rage, hope, deliverance and what Aime Cesaire called “poetic knowledge.” Because if hip-hop is insurgent cultural war, then peep the strategies and tactics of every kind of guerilla war in history and you’ll see that they’re won or lost by the range of their attacks, the diversity of their methods, and the conviction of their beliefs. Lets just hope it ain’t too late…